Will the NFL Ever Stop Manufacturing Passing Efficiency?

Three weeks and 48 games into the 2018 regular season, we are witnessing the greatest increase in passing efficiency in the post-merger NFL. The NFL’s business model is clear: They want high-flying, frequent scoring games. The question now is if it sustainable.

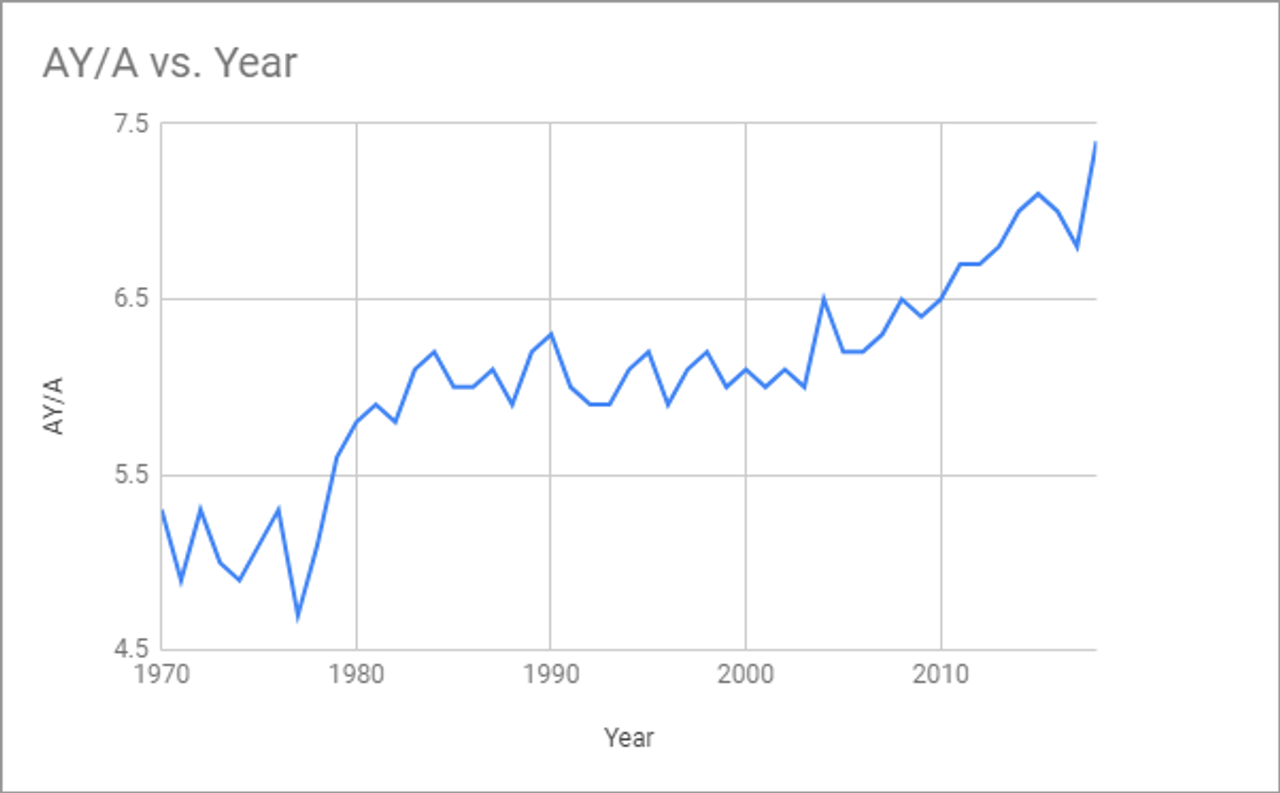

To understand how drastically passing efficiency has increased this year, let’s take a look at what amounts to the three eras of passing efficiency from an Adjusted Yards per Attempt (AY/A) perspective. AY/A is a stat that treats passing touchdowns as a tacked on 20 yards and interceptions as losses of 45 yards on top of your basic yards per pass attempt numbers. Adjusted Net Yards per Attempt (ANY/A) is AY/A accounting for sacks and sack yards and is the passing stat most correlated with wins. For this example, though, I want to look at AY/A because I personally believe that sacks and sack yards, while often swinging games and notable at the team projection level, are more products of coaching, schemes and protections than a stat owned by quarterbacks.

Era 1: 1970-1977

Until 1978, NFL offensive linemen were not allowed to block with open hands nor were they allowed to extend their arms. As you can imagine, the lack of modern pass protection rules drastically influenced the frequency of pressure that quarterbacks were facing. Over the first eight years of the post-merger NFL, AY/A ranged from 4.7, the low in 1977, to 5.3.

Era 2: 1978-2003

After what amounts to a “dead ball era” to start the post-merger NFL, passing efficiency jumped every year from 1978 to 1981 following the rule changes for offensive linemen. After stabilizing around 1980, the sport basically looked the same for over two decades. For reference, the difference between AY/A in 1980 (5.8) and 2003 (6.0) was just 0.2, one-sixth of the increase from 1977 (4.7) to 1981 (5.9). The same NFL that Terry Bradshaw peaked in was the one Peyton Manning was drafted into. It was naturally stabilized.

After what amounts to a “dead ball era” to start the post-merger NFL, passing efficiency jumped every year from 1978 to 1981 following the rule changes for offensive linemen. After stabilizing around 1980, the sport basically looked the same for over two decades. For reference, the difference between AY/A in 1980 (5.8) and 2003 (6.0) was just 0.2, one-sixth of the increase from 1977 (4.7) to 1981 (5.9). The same NFL that Terry Bradshaw peaked in was the one Peyton Manning was drafted into. It was naturally stabilized.

Era 3: 2004-Present

This is where we see constant rule changes. The enforcement of defensive pass interference, defensive holding and illegal use of hands led to an immediate increase in passing efficiency that had not been seen since the NFL changed the rules for how offensive linemen can legally block. Subsequent rule changes, protecting quarterbacks in the pocket, have increased passing efficiency from 6.0 in 2003 to 7.4 in 2018.

This is where we see constant rule changes. The enforcement of defensive pass interference, defensive holding and illegal use of hands led to an immediate increase in passing efficiency that had not been seen since the NFL changed the rules for how offensive linemen can legally block. Subsequent rule changes, protecting quarterbacks in the pocket, have increased passing efficiency from 6.0 in 2003 to 7.4 in 2018.

At the moment, there seem to be no signs of the NFL disincentivizing rule changes in favor of passing efficiency. Unlike the previous eras, these numbers have not stabilized but are constantly climbing. You might even be able to make the case that the era stabilized from 2011 to 2017, but that the 2018 rule change for roughing the passer actually ushered in what could be the fourth era of passing efficiency. We would certainly need more than just three weeks of data, but it's worth noting the start to the 2018 season.

---

This is where we get to the question of sustainability. This is also when another change, the lack of practice time since the 2011 collective bargaining agreement, becomes important. Between 2004 and 2010, after the enforcement of defensive backs was emphasized but before practice time was slashed, we saw the beginnings of the peaks of Drew Brees, Aaron Rodgers, Ben Roethlisberger, Philip Rivers, Tony Romo and Matt Ryan, who along with the then-recent emergences of Peyton Manning and Tom Brady and the tail end of the careers of Kurt Warner and Brett Favre brought in “the golden age of quarterbacks.”

These quarterbacks benefitted from rules that extended their development with practice time, rules that allowed their passing efficiency to increase naturally and rules that extended their careers by keeping them healthy in the pocket. When Joe Montana retired in 1995, he was celebrated as an outlier for his 192-start career. Players like Favre (302), Manning (266), Brady (256), Roethlisberger (203) and Rivers (200) have already passed him in Era 3, with the likes of Ryan and Rodgers on a crash course to leap him in the near future.

This is all to say that not only have the efficiency numbers that quarterbacks have passed for changed but so do the frequency of games that they are projected to start. Before the third era of passing efficiency, it was almost impossible to find more than a ten-year peak for a passer. Now, the expectation for star quarterbacks is 15-plus years, all while quarterbacks are also throwing more frequently per game.

Related: Using 2018 Fantasy Projections to Create On-Field Quarterback Tiers

This is important to note because the NFL’s 2011 change to practice time has almost certainly influenced its ability to develop quarterbacks. Since 2011, among passers with 400 or more pass attempts, only two of the top ten passers, from an AY/A perspective, have been new faces to the league. This means that over the last eight years of NFL football, only two quarterbacks have emerged who have played what amounts to a year as a full-time starter and also outpace Alex Smith’s passing efficiency since 2011. The only 2011-2018 class quarterbacks with 400 or more passes and an AY/A above Colin Kaepernick, a quarterback often criticized for his stats since he has left the NFL, are Russell Wilson, Jared Goff and Kirk Cousins. Mind you, the teams that started Smith and Cousins at quarterback in 2017 both moved on from them this offseason.

Since 2004, the NFL has simultaneously made the passing game more important while making the development of difference-making passers less likely. If you were lucky enough to develop a quarterback from 2004 to 2010, you are probably still a consistent contender to date. This is a product of how the NFL has changed in the last 15 years.

Related: How "Football Experts" Gamble on Sports

When Brady, Roethlisberger and Rivers join Manning and Romo in retirement soon, is the NFL banking on the likes of a Cousins to be a top-five quarterback in the league? Recent draft picks have generated hope for franchise quarterbacks, but little to show for it. Blake Bortles, Carson Wentz, Dak Prescott, Derek Carr, Deshaun Watson, Jimmy Garoppolo, Josh Allen, Marcus Mariota, Mitch Trubisky and Sam Darnold, all starting quarterbacks who have been drafted since 2013, have combined for 844 pass attempts, 5,995 yards, 27 passing touchdowns and 28 interceptions, good for an AY/A of 6.3, roughly equal to the career AY/A of Kyle Orton, Jason Campbell and Sam Bradford. Disproportionately, passing efficiency is being propped up by passers groomed in that 2004-2010 window, not new quarterbacks and the NFL cannot live off them forever.

While the recent success of Patrick Mahomes (AY/A: 12.4) and Baker Mayfield (AY/A: 8.7) provides hope for the future stars of the league, they have still only thrown a combined 151 passes in the NFL. The lack of pro quarterback development since 2011, only emphasized more by the fact that first-round picks were spent on quarterbacks Paxton Lynch, Johnny Manziel, Teddy Bridgewater, E.J. Manuel, Robert Griffin, Brandon Weeden, Jake Locker, Blaine Gabbert and Christian Ponder who are not currently starters, is going to hurt the NFL if their plan really is for a yearly rise in scoring.

Related: Patrick Mahomes, Ryan Fitzpatrick and Hot Starts

With only really two quarterbacks (Wilson and Goff) developed to be certain stars over the last eight drafts, with a few (Mahomes, Mayfield, etc.) in the mix as rising stars, the NFL must either set its sights lower for constantly rising scoring projections, plan to constantly change rules to keep up with retiring quarterback talent or make it a point to give quarterbacks more practice time in the 2021 collective bargaining agreement. At the moment, nothing about NFL passing efficiency rising is self-sustaining. It is all held up by ever-changing rules and quarterbacks who were developed in a short window a decade ago. The reason why the NFL does not "look like it used to" is because it is trying to overcompensate for its lack of quarterback development while also attempting to increase scoring on a yearly basis.